The Ladder of Inference

The Ladder of Inference is a model first introduced by Chris Argyris and Peter Senge that puts forward a structure of how our brains move from absorbing information through to a final decision or action, and the steps involved in this process. Normally, we climb up this ladder without realising we are taking each step. Our brain is designed to process information at such a rapid pace that we are often unaware of all the minutiae involved in a final decision. And, as we know, we can process thousands of thoughts each day, and thus this process is happening at an astonishing rate.

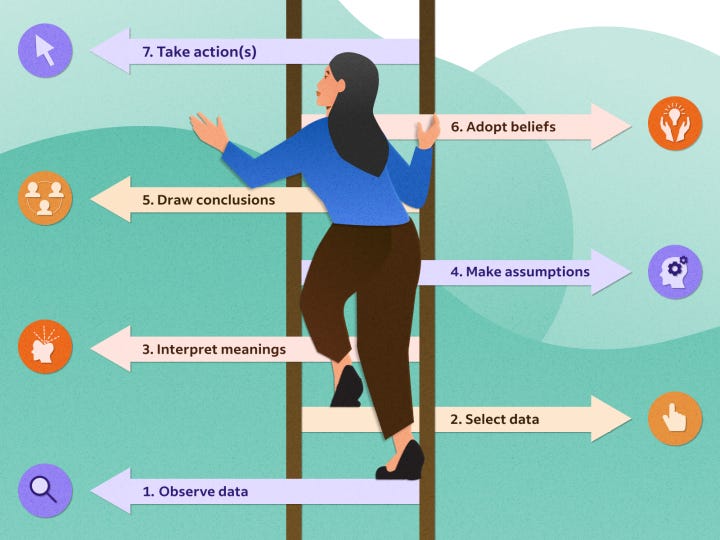

The Ladder of Inference is composed of seven steps, or seven ‘rungs’. It is useful to visualise this ladder, or alternatively watch one of the vi

deos online if you require a distinct visual stimulus. I want you to imagine that this ladder is sat in the imaginary zone of our subconscious within our brain. Throughout every interaction we have with an individual, or even any situation we process, the experience enters the ladder at the bottom. This experience then zips up the ladder in a flash, before exiting at the top. Each rung of the ladder has a specific function for our experience, and each rung can have a large impact on how our brain processes this experience.

Rung one is simply the processing of raw data. It is observational, almost what it would be like as a first-person video game of our life. Rung two of the ladder is the filtering stage. This is where our brain filters specific information from the experience. However, this filter occurs unknowingly and is based on our preferences, tendencies and other things we feel are important. What we filter may also be impacted by our physiological state - for example we may filter less information when we are more fatigued.

Rung three of the ladder is where we start to attach meaning to the information we have filtered from our experience. This phase is where we begin to interpret what we have filtered through. Rung four is where we make our assumptions regarding the experience. We develop these assumptions based on the meaning we have generated on the previous rung of the ladder. Here, we may begin to blur the lines between what is fact, and what is fiction. Rung five of the ladder involves drawing our conclusions on the experience that has occurred. Again, this is based on the assumptions we have drawn on rung four. Furthermore, rung five is where we add an emotional attachment or reaction to the experience.

Rung six is where we adjust our beliefs regarding the situation we are in. This may involve adjustments towards a person or people involved in the experience, or an adjustment of an idea or certain knowledge we have of the world. Finally, rung seven is where we reach our decision or our action, based on our adjusted beliefs.

In my opinion, this model hits a slight flaw in the final rungs of the ladder. I believe rung six and seven do not inherently occur in that order. When we are processing information, particularly at a rapid rate, we can take action before we have even considered our beliefs. Of course action or a decision is a key final step in this ladder, but often we may not wait to adjust our beliefs in order to take action. However, the model still is a brilliant metaphor for how our brain processes information, and only one of Chris Argyris and I had an illustrious career as a professor at Yale and Harvard Business School. I’ll let you guess who.

Let’s take a look at a real life example to better understand how the ladder of inference works during our day to day. In this scenario I want you to imagine that you are on your morning walk to work. Suddenly, you are cut up on your path by someone pushing past you in a hurry, forcing you to abruptly stop in your path for a second. Here’s what happens at each step of the ladder:

Data: You observe that you are walking along the path. You observe that you are cut up by someone. You observe that you have to stop abruptly.

Filtering: You filter the details that the person who pushed past you was a man in a suit, wearing an estate agency puffa jacket. You see that they are continuing to walk down the street in a hurry. You acknowledge the clenching of your fists and increase in heart rate. Importantly, you filter out the information that it’s surprisingly a sunny day, the birds are chirping and there’s a 50% off sale sign in your favourite shop to your left.

Meaning: Growing up you were told to be kind and anyone who pushes you must be rude with no manners. You believe that no one should push past someone when they are walking, as they can simply say ‘excuse me’. Your friends growing up always told you they dislike estate agents because they are sleazy and will do anything to make a sale.

Assumptions: You make the assumption that this man did not learn about being kind growing up, and he must have no manners. He must not be paying any attention because he is so self-centred. He must be too absorbed in his life as a sleazy estate agent to care about anyone else.

Conclusions: You conclude that this is a rude, heartless man who never pays any attention and does not know what it means to be kind or have manners. You conclude that he cares more about making a sale for his estate agency than any human, and his sleazy demeanour matches the previous stories from your friends.

Adjust beliefs: You adjust your beliefs towards the understanding that all estate agents are sleazy, rude and have no manners.

Action: A decision is made to shout out at the man, “Hey dickhead! Watch where you’re going you little bitch.”

Finally we have reached the final rung of the ladder. Now following this final decision and action, you may feel a bit better for shouting out at the man. Yet ultimately, you have generated a lot of negativity, and despite one potential brief instance of satisfaction from calling a grown man a little bitch, you are always going to end up feeling pretty crap about ourselves. Negative actions breeds negativity in our mind, and you are in a position here where you may be in a bad mood for the next hour. Even more so, you have created a dangerous addition to your belief that all estate agents are sleazy, and they are all rude with no manners.

Now, are there sleazy estate agents who are rude and have no manners? Absolutely. But the same could be said for absolutely anyone, in any industry. We may all have some pre-established beliefs about estate agents, but how much of it is fuelled by pure fact and not a story created through a woven map of previous meaning and assumptions? How do you know what your friends told you about estate agents was fact, and not fuelled by assumptions, exaggerations and misplaced emotions?

“Well my brother Johnny had a mate whose cousin was completely ripped off by a sleazy estate agent, and he lost out on a house because of him”. This is hardly a far cry from a story one of our friends could have told us. Typically, we may not batter an eye at this story, particularly if our friend is someone we trust. Without really knowing, we may have processed this data up our ladder of inference and adjusted to our beliefs. Our beliefs now hold information that estate agents can be sleazy, so much so that we could lose a house because of it. And what do you think the outcome to our beliefs would be if we heard three or four stories from people in our lives?

But what if we were to find out that in this story about the sleazy estate agent, the loss of the house actually came from a family in the property chain pulling out of the house sale. The estate agent actually had fought long and hard for Johnny’s mate’s cousin to still be in a chance to purchase the house, spending many hours of overtime trying to persuade the family not to pull out. He had actually spoken to his manager to give Johnny’s mate’s cousin a better deal because he saw that he was in a financially difficult place. Yet ultimately, the story got passed on and the loss of the house suddenly became attached to the role of the estate agent. We all know the power of Chinese whispers, and it is certainly believable for these situations to snowball out of control. And before you know it, you have a small addition to your beliefs around estate agents, which has stemmed from data that was completely false.

You can see how previous experiences have adjusted our beliefs in a particular direction. And so, when this rude man pushes past us, and we process the information up our ladder of inference, our beliefs have already been biassed towards certain assumptions. Our biassed filtering mechanism causes us to attach a certain meaning from our past, which further impacts the assumptions and conclusions we make, and ultimately the action we take. But we know that this is based on stories, not pure fact. As much as we think we are right and purely objective, this is not the case. “We see the world not as it is, but as we are - Covey”.

So let’s develop the scenario further. What if you were to learn that the estate agent who pushed past you is rushing not on his way to work, but on the way to hospital because his wife has been in a car accident? He is told he needs to get to the hospital immediately, and there is a chance his wife could die. When you shout out at him, he apologises profusely in a trembling voice explaining the above. You then end up feeling pretty awful for calling him a little bitch, causing you to apologise profusely, wishing him all the best on his way to the hospital.

Ultimately, you have created a scenario of negativity that could have been avoided. You have likely upset someone who was already facing a whirlpool of challenging emotions. Had you learned the information that this man was rushing to the hospital to see his wife following the car accident, I’m sure the thought to shout out at him would not have even entered your mind.

And herein lies a powerful opportunity to rethink how we think. The next time a situation like this occurs, whether it is someone cutting you up in the street, taking a parking space you intended to use, or perhaps even a group of friends annoying you on the train by laughing and chatting too loudly - consider what has happened on the steps in your ladder. What data have you filtered in and importantly out, and why do you think that has happened? What meaning have you attached to the situation? What assumptions have you concluded, and were they factual or a story? Were your conclusions fuelled by pre-established beliefs? How accurate are those beliefs? Are your emotional attachments valid or have they been blown out of proportion? Are your final decisions and actions an accurate representation of the situation, or have they been exacerbated by all of the before?

Then, with some targeted thoughts and internally directed questions, you may be able to find out where and how you are exacerbating your actions, and where the line between fact and fiction is being blurred. Some of us actually focus on certain rungs of our ladder during our day without realising it. “I’m sorry for getting upset, I’m just hungry. I didn’t mean it.” This is a beautiful example of looking at rung number 5, to realise that we have added an emotional attachment because we were hungry, and nothing more. I’m sure we can all appreciate how being hungry affects our decisions and actions. This exercise of analysing the steps on our ladder is simply a more in-depth and built-on method of realising and acknowledging that our actions can be influenced by our hunger.

And there we have a quick summary of how to use The Ladder of Inference model to understand how our brain is processing information, and which steps we might want to look into to ascertain where we need to reframe our mindset.

Happy Laddering!